Introduction

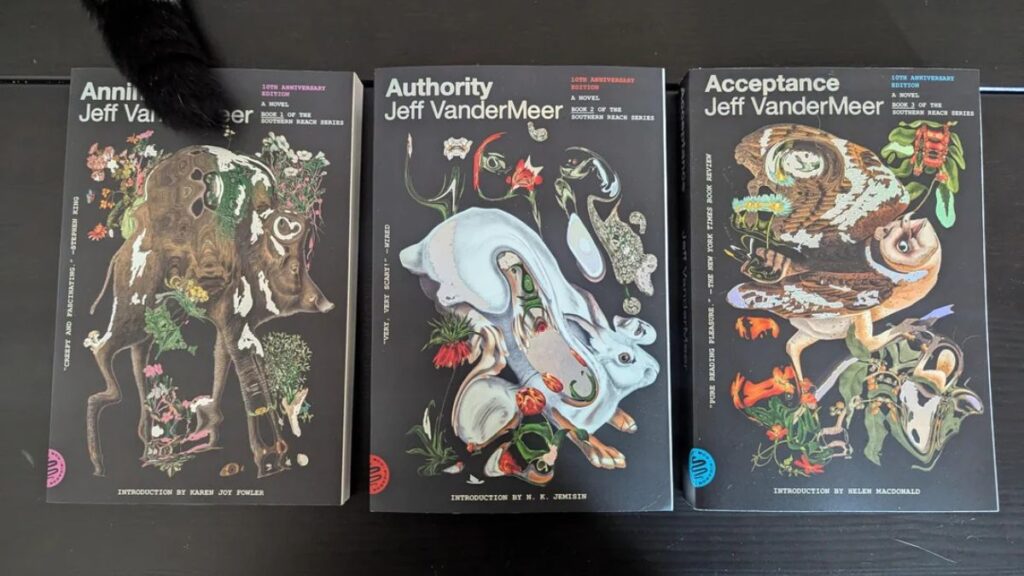

Let’s face it: nothing quite hits like a novel that dissolves your sense of reality and drapes you in an atmosphere so meticulously uncanny that by the final page, you’re questioning every shadow in your home. Enter the annihilation book, Jeff VanderMeer’s 2014 masterstroke that launched the Southern Reach trilogy and redefined contemporary eco-horror. Here, hectares of mutated flora hide eldritch forces; a cadre of unnamed explorers—only known as the Biologist, the Psychologist, the Surveyor, and the Anthropologist—embark on a mission to map the enigmatic Area X. What they find is an annihilation of the boundaries between the human and the nonhuman, an unsettling dance of ecology and erasure.

VanderMeer didn’t just pen a thriller; he sculpted a living organism of prose that pulses with ambiguity and tentacular unease. In this piece, we’ll plunge into the heart of the annihilation book: its origins, narrative alchemy, thematic richness, and cultural aftershocks. Buckle up—this isn’t just a book review. It’s a descent into the green haze.

Jeff VanderMeer: Architect of the Uncanny

To grasp the annihilation book’s full heft, you’ve got to start with its architect, Jeff VanderMeer. Long a luminary in speculative fiction circles, VanderMeer’s résumé bristles with boundary-pushing novellas, short stories, and he brings a background steeped in environmental activism and southern gothic traditions. Growing up in the American South, he experienced landscapes where natural beauty masked darker undercurrents—a duality he now channels into his fiction.

Before Area X, VanderMeer’s 2009 anthology The Southern Reach (later retitled Annihilation) was already stirring whispers. His fascination with ecological collapse, invasive species, and the blurred line between flora and fauna matured in the pages of magazines like Weird Tales. By the time the annihilation book hit shelves, readers were primed for an eco-nightmare that didn’t feel like an afterthought but rather the culmination of years spent interrogating humanity’s fragile dominion over the wild.

Mapping the Unknowable: Plot Overview

Spare yourself spoilers beyond the bare bones: the annihilation book kicks off with a fourth expedition into Area X, a coastal zone quarantined after decades of inexplicable phenomena. The Southern Reach—a shadow agency of underfunded eccentrics—dispatches four women, each chosen for her specialty. Our protagonist, the Biologist, narrates with clinical detachment, slowly peeling back layers of her own psyche as she documents bizarre spores, ghostly structures, and a tower that rewrites her understanding of space.

Unlike your average hero’s journey, this narrative is an exercise in unknowing. Pages drip with vines that crawl like sentient tendrils; mushrooms bloom in impossible geometries; the sea exerts an almost sentient memory. The expedition unravels under the weight of secrecy, paranoia, and the palpable sense that Area X is not merely a location but a living, thinking organism. By the climax, the annihilation book doesn’t just catalog horrors—it reenacts them, contorting the reader’s certainty into something eerily pliable.

Narrative Alchemy: Voice and Structure

What elevates the annihilation book from pulpy horror to literary crucible is its magnetic narrative voice. VanderMeer ditches names in favor of function: the Biologist, the Psychologist, the Surveyor, the Anthropologist. This deliberate anonymity turns characters into archetypes, forcing us to confront the roles we assign in crises—observer, interpreter, mapper, colonizer. The Biologist’s interior monologue, marked by precise scientific lexicon, spirals into poetic introspection as Area X seeps into her consciousness.

Structurally, the annihilation book shuns conventional chapters. Instead, we navigate through numbered sections, each paired with field journal entries, recovered documents, and fragments of classified memos. This collage technique amplifies the mystery: one moment you’re digesting clinical bullet points on fungal DNA, the next you’re immersed in dreamlike hallucinations that resist linear time. The result? A narrative alchemy that transmutes fear into fascination, horror into haunting beauty.

Themes and Motifs: More Than Just Monsters

At first glance, the annihilation book is about monstrous landscapes and biotech gone rogue. Yet at its core, it probes questions that linger long after you close the spine:

-

Ecological Reckoning: Area X is nature’s grand experiment—an ecosystem untainted by human intervention, but also unrecognizable to our classifications. VanderMeer implicitly asks: do we deserve dominion over the planet, or are we merely gatecrashers in evolutionary history?

-

Identity and Transformation: As the Biologist’s mission progresses, she notices subtle shifts in her perception and physiology. What happens when the observer becomes the observed? The annihilation book waltzes with body horror and existential dread, suggesting that transformation is both our greatest fear and inevitable fate.

-

The Unknowable Other: From the spindly fungus towers to the spectral lights in the trees, Area X embodies the otherness we strive to categorize and control, only to realize some mysteries defy taxonomy. This motif resonates with broader cultural anxieties—climate change, pandemics, artificial intelligence—realms where our ignorance is an Achilles’ heel.

-

Authority and Secrecy: The Southern Reach’s opaque bureaucracy mirrors real-world institutions that hoard knowledge under the guise of security. VanderMeer skewers this pretense, implying that true understanding demands radical transparency—even if, paradoxically, full disclosure risks unleashing chaos.

The Ecology of Fear

Horror stories often rely on jump scares or grotesque imagery; the annihilation book relies on atmosphere—an ecosystem of dread that grows organically. Think fungal networks that connect trees like neural pathways, or a “tower” that defies Euclidean geometry, its walls breathing with bioluminescent organisms. Each description is a brushstroke, painting Area X as a character unto itself: seductive, inscrutable, and lethal.

VanderMeer’s prose simmers with sensory detail. The Biologist’s nasal passages sting with spores; her skin prickles at subtle shifts in humidity; the glint of sunlight off living crystal leaves etches itself into her mind. It’s a master class in ecological horror: you don’t need to see a monster to feel its presence. The annihilation book’s genius is in cultivating dread through the lens of the nonhuman, reminding us that Earth’s other inhabitants have survived millennia without our sentimental spotlight.

Critical Reception and Impact

Upon release, the annihilation book garnered a chorus of acclaim, earning a Nebula Award nomination and clinching the Shirley Jackson Award for best novel. Critics lauded its unprecedented fusion of literary subtlety and genre thrills—a recognition that an eco-horror rooted in environmental consciousness was overdue. Publications like The Guardian hailed it as “a visceral elegy for a dying world,” while GQ praised its “quiet, relentless terror” that lingered long after the final page.

Its impact reverberated beyond literary circles. Environmentalists cited Area X as a stark allegory for climate change’s unpredictable feedback loops; philosophers mused on its meditations on selfhood and agency; filmmakers eyed its cinematic potential. The annihilation book proved that speculative fiction could be both artful and urgent—a clarion call to reimagine our relationship with the planet.

From Page to Screen: The 2018 Adaptation

In 2018, director Alex Garland—a maestro of cerebral sci-fi (Ex Machina, Never Let Me Go)—unveiled a film adaptation of the annihilation book. Starring Natalie Portman as Lena (the Biologist’s analogue), the movie distilled VanderMeer’s fever dream into a visceral visual experience. Garland captured the book’s kaleidoscopic horror: phosphorescent landscapes, unnatural plant hybrids, and a climactic confrontation with the zone’s mutable heart.

Yet the film diverges in pivotal ways. It compresses the narrative, sequencing Lena’s journey in a tighter, more personal arc; it amplifies the theme of grief and guilt, framing the expedition as both external and internal odyssey. While purists quibbled at the changes, many lauded Garland’s adaptation as a companion piece rather than a reductive translation. After all, the annihilation book thrives on suggestion and ambiguity—an elusive tone that Garland honored through haunting imagery and restrained exposition.

Legacy and Influence

Seven years on, the annihilation book remains a lodestar in speculative fiction. Its legacy unfolds across genres: contemporary eco-horror novels echo its atmospheric dread; television anthologies borrow its structural collage; video game designers cite Area X as inspiration for open-world zones that shift and react to player choices. Universities even offer seminars on “Eco-Weird Fiction,” where the annihilation book sits front and center alongside Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Word for World Is Forest and Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World.

But perhaps its most enduring influence is philosophical: VanderMeer reminds us that the line between self and world is porous, that the narratives we construct about nature shape our destiny. In an era of unprecedented ecological upheaval, the annihilation book doesn’t just entertain—it provokes. It asks: can we embrace uncertainty? Can we relinquish our illusion of control? And if we fail, will the planet forgive us?

Conclusion: Embracing the Unknown

The annihilation book is no comfort read. It offers no tidy resolutions, no triumphant hero’s return. Instead, it immerses you in a vast, breathing enigma where the real horror is not monstrous creatures but the dissolution of certainties we hold dear. VanderMeer’s prose demands surrender—to the unknown, to the nonhuman, to change itself.

As you step away from Area X—closing the final page with trembling fingers—you carry a seed of its uncanny logic. You might find yourself drawn to forest trails with fresh eyes, wondering what intelligence lurks beneath the moss. You might question whether the soil beneath your feet is silent or simply biding its time. Above all, you understand that genuine fascination has teeth: it nibbles at complacency until transformation is no longer a metaphor but an annihilation of yesterday’s constraints.

And isn’t that, after all, the most exhilarating kind of reading? The annihilation book doesn’t just tell a story. It invites you to become part of something alive, a verdant unknown stretching beyond the page—beckoning, unsettling, utterly unforgettable.